New Party (UK) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The New Party was a political party briefly active in the United Kingdom in the early 1930s. It was formed by

On 28 February 1931 Mosley resigned from the Labour Party, launching the New Party the following day. The party was formed from six of the Labour MPs who signed the Mosley Manifesto (Mosley and his wife, Baldwin, Brown, Forgan and Strachey), although two (Baldwin and Brown) resigned membership after a day and sat in the

On 28 February 1931 Mosley resigned from the Labour Party, launching the New Party the following day. The party was formed from six of the Labour MPs who signed the Mosley Manifesto (Mosley and his wife, Baldwin, Brown, Forgan and Strachey), although two (Baldwin and Brown) resigned membership after a day and sat in the

Sir Oswald Mosley

Sir Oswald Ernald Mosley, 6th Baronet (16 November 1896 – 3 December 1980) was a British politician during the 1920s and 1930s who rose to fame when, having become disillusioned with mainstream politics, he turned to fascism. He was a member ...

, an MP who had belonged to both the Conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization i ...

and Labour

Labour or labor may refer to:

* Childbirth, the delivery of a baby

* Labour (human activity), or work

** Manual labour, physical work

** Wage labour, a socioeconomic relationship between a worker and an employer

** Organized labour and the labour ...

parties, quitting Labour after its 1930 conference narrowly rejected his " Mosley Memorandum", a document he had written outlining how he would deal with the problem of unemployment.

Mosley Memorandum

On 6 December 1930, Mosley published an expanded version of the "Mosley Memorandum", which was signed by Mosley, his wife and fellow Labour MP Lady Cynthia and 15 other Labour MPs: Oliver Baldwin,Joseph Batey

Joseph Batey (4 March 1867 – 21 February 1949) was a Labour Party politician in the United Kingdom.

Batey became a coal miner, before winning election as a checkweighman, and then becoming a full-time official for the Durham Miners' Associat ...

, Aneurin Bevan

Aneurin "Nye" Bevan PC (; 15 November 1897 – 6 July 1960) was a Welsh Labour Party politician, noted for tenure as Minister of Health in Clement Attlee's government in which he spearheaded the creation of the British National Health ...

, W. J. Brown, William Cove

William George Cove (21 May 1888 – 15 March 1963) was a British politician. He served as a Labour Party Member of Parliament (MP) from 1923 to 1959.

Cove was born in Halifax Terrace, Middle Rhondda, to Edwin and Elizabeth Cove. His father, a ...

, Robert Forgan

Robert Forgan (10 March 1891 – 8 January 1976) was a British politician who was a close associate of Oswald Mosley.

Early life and medical career

The Scottish-born Forgan was the son of a Church of Scotland minister.Dorril, p. 151 Educated up ...

, J. F. Horrabin

James Francis "Frank" Horrabin (1 November 1884 – 2 March 1962) was an English socialist and sometimes Communist radical writer and cartoonist. For two years he was Labour Member of Parliament for Peterborough. He attempted to construct a s ...

, James Lovat-Fraser

James Alexander Lovat-Fraser (16 March 1868 – 18 March 1938) was a British Labour Party and then National Labour politician. He sat in the House of Commons from 1929 to 1938.

He unsuccessfully contested Llandaff and Barry at the 1922 genera ...

, John McGovern, John James McShane

John James McShane (1 October 1882 – 26 May 1972) was a British school teacher and Labour politician.

Early life

He was born in Wishaw, Lanarkshire, Scotland, and was the son of Philip McShane, a coalminer, and his wife Bridget. Both his paren ...

, Frank Markham

Sir Sydney Frank Markham (19 October 1897 – 13 October 1975) was a British politician who represented three constituencies, each on behalf of a different party, in Parliament.

Born in Stony Stratford, he left school at the age of fourteen. ...

, H. T. Muggeridge, Morgan Philips Price

Morgan Philips Price (29 January 1885 – 23 September 1973) was a British politician and a Labour Party Member of Parliament (MP).

He was born in Gloucester. His father, William Edwin Price, was also a British MP, serving for the seat of Tewkes ...

, Charles Simmons Charles Simmons may refer to:

*Charles Simmons (gymnast) (1885–1945), British gymnast who competed in the 1912 Summer Olympics

*Charles Simmons (author) (1924–2017), American editor and novelist

*Charles Simmons (author, born 1798), American cl ...

, and John Strachey. It was also signed by A. J. Cook

Andrea Joy Cook (born July 22, 1978) is a Canadian actress. She is best known for her role as Supervisory Special Agent Jennifer "JJ" Jareau on the CBS crime drama ''Criminal Minds'' (2005–2020, 2022). Cook has also appeared in ''The Virgin ...

, general secretary

Secretary is a title often used in organizations to indicate a person having a certain amount of authority, power, or importance in the organization. Secretaries announce important events and communicate to the organization. The term is derived ...

of the Miners' Federation of Great Britain

The Miners' Federation of Great Britain (MFGB) was established after a meeting of local mining trade unions in Newport, Wales in 1888. The federation was formed to represent and co-ordinate the affairs of local and regional miners' unions in Engla ...

.

Founding the New Party

On 28 February 1931 Mosley resigned from the Labour Party, launching the New Party the following day. The party was formed from six of the Labour MPs who signed the Mosley Manifesto (Mosley and his wife, Baldwin, Brown, Forgan and Strachey), although two (Baldwin and Brown) resigned membership after a day and sat in the

On 28 February 1931 Mosley resigned from the Labour Party, launching the New Party the following day. The party was formed from six of the Labour MPs who signed the Mosley Manifesto (Mosley and his wife, Baldwin, Brown, Forgan and Strachey), although two (Baldwin and Brown) resigned membership after a day and sat in the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. ...

as independent MPs; Strachey resigned in June. The party received £50,000 funding from Lord Nuffield

William Richard Morris, 1st Viscount Nuffield, (10 October 1877 – 22 August 1963) was an English motor manufacturer and philanthropist. He was the founder of Morris Motors Limited and is remembered as the founder of the Nuffield Foundation, ...

and launched a magazine called ''Action'', edited by Harold Nicolson

Sir Harold George Nicolson (21 November 1886 – 1 May 1968) was a British politician, diplomat, historian, biographer, diarist, novelist, lecturer, journalist, broadcaster, and gardener. His wife was the writer Vita Sackville-West.

Early lif ...

. In addition, Nicolson produced a New Party propaganda film titled ''Crisis'' and aimed to get it shown in the cinemas but the censors banned the film as it was considered it would "bring Parliament into disrepute" due to its depiction of MPs asleep on the benches. In the event the film was only shown at New Party meetings.

Mosley also set up a party militia, the "Biff Boys" led by the England rugby

The England national rugby union team represents England in men's international rugby union. They compete in the annual Six Nations Championship with France, Ireland, Italy, Scotland and Wales. England have won the championship on 29 occasions ...

captain Peter Howard.

The New Party's first electoral contest was at the Ashton-under-Lyne by-election in April 1931. The candidate was Allan Young, and his election agent

An election agent in elections in the United Kingdom, as well as some other similar political systems such as elections in India, is the person legally responsible for the conduct of a candidate's political campaign and to whom election material is ...

was Wilfred Risdon

Wilfred Risdon (28 January 1896 – 11 March 1967) was a British trade union organizer, a founder member of the British Union of Fascists and an antivivisection campaigner. His life and career encompassed coal mining, trade union work, First W ...

. With a threadbare organisation they polled some 16% of the vote, splitting the Labour vote and allowing a Conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization i ...

to be returned to the Commons. Two more MPs joined the New Party later in 1931: W. E. D. Allen

William Edward David Allen (6 January 1901 – 18 September 1973) was a British scholar, Foreign Service officer, politician and businessman, best known as a historian of the South Caucasus—notably Georgia (country), Georgia. He was closely in ...

from the Unionists and Cecil Dudgeon

Cecil Randolph Dudgeon (7 November 1885 – 4 November 1970) was a Scottish Scottish Liberal Party, Liberal Member of Parliament (United Kingdom), Member of Parliament (MP) who joined Oswald Mosley's New Party (UK), New Party.

He was elected at ...

from the Liberals. At the 1931 general election the New Party contested 25 seats, but only Mosley himself, and a candidate in Merthyr Tydfil

Merthyr Tydfil (; cy, Merthyr Tudful ) is the main town in Merthyr Tydfil County Borough, Wales, administered by Merthyr Tydfil County Borough Council. It is about north of Cardiff. Often called just Merthyr, it is said to be named after Tydf ...

(Sellick Davies stood against only one Independent Labour Party

The Independent Labour Party (ILP) was a British political party of the left, established in 1893 at a conference in Bradford, after local and national dissatisfaction with the Liberals' apparent reluctance to endorse working-class candidates ...

(ILP) candidate in Merthyr, while Mosley stood against both Conservative and Labour candidates in Stoke) polled a decent number of votes, and three candidates lost their deposits. Mosley's New Party general election campaign received prominent press coverage in various national newspapers during 1931 with ''The Manchester Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'', and changed its name in 1959. Along with its sister papers ''The Observer'' and ''The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardian'' is part of the Gu ...

'' reporting that "The stewards were wearing rosettes of black and amber – the Mosley colours. Busy bees, hiving the honey of prosperity? That may be the symbolism of it."

Policies

The New Party programme was built on the "Mosley Memorandum", advocating a national policy to meet the economic crisis that theGreat Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

had brought. His desire for complete control of policy making decisions in the New Party led many members to resign membership. He favoured granting wide powers to the government, with only general control by Parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

, and creating a five-member Cabinet

Cabinet or The Cabinet may refer to:

Furniture

* Cabinetry, a box-shaped piece of furniture with doors and/or drawers

* Display cabinet, a piece of furniture with one or more transparent glass sheets or transparent polycarbonate sheets

* Filing ...

without specific portfolio, similar to the War Cabinet

A war cabinet is a committee formed by a government in a time of war to efficiently and effectively conduct that war. It is usually a subset of the full executive cabinet of ministers, although it is quite common for a war cabinet to have senior ...

adopted during the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

. His economic strategy broadly followed Keynesian

Keynesian economics ( ; sometimes Keynesianism, named after British economist John Maynard Keynes) are the various macroeconomic theories and models of how aggregate demand (total spending in the economy) strongly influences economic output and ...

thinking and suggested widespread investment into housing to provide work and improve housing standards overall and also supporting protectionism

Protectionism, sometimes referred to as trade protectionism, is the economic policy of restricting imports from other countries through methods such as tariffs on imported goods, import quotas, and a variety of other government regulations. ...

with proposals for high tariff

A tariff is a tax imposed by the government of a country or by a supranational union on imports or exports of goods. Besides being a source of revenue for the government, import duties can also be a form of regulation of foreign trade and poli ...

walls.

Demise

After the election, Mosley toured Europe and became convinced of the virtues offascism

Fascism is a far-right, authoritarian, ultra-nationalist political ideology and movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and political and cultural liberalism, a belief in natural social hierarchy an ...

. Gradually, the New Party became more authoritarian, with parts of it, notably its youth movement NUPA, adopting overtly fascist thinking and the wearing of "Greyshirt" uniforms.Worley, Matthew (2010). ''Oswald Mosley and the New Party''. Palgrave MacMillan. The New Party's sharp turn to fascism led previous supporters such as John Strachey and Harold Nicolson

Sir Harold George Nicolson (21 November 1886 – 1 May 1968) was a British politician, diplomat, historian, biographer, diarist, novelist, lecturer, journalist, broadcaster, and gardener. His wife was the writer Vita Sackville-West.

Early lif ...

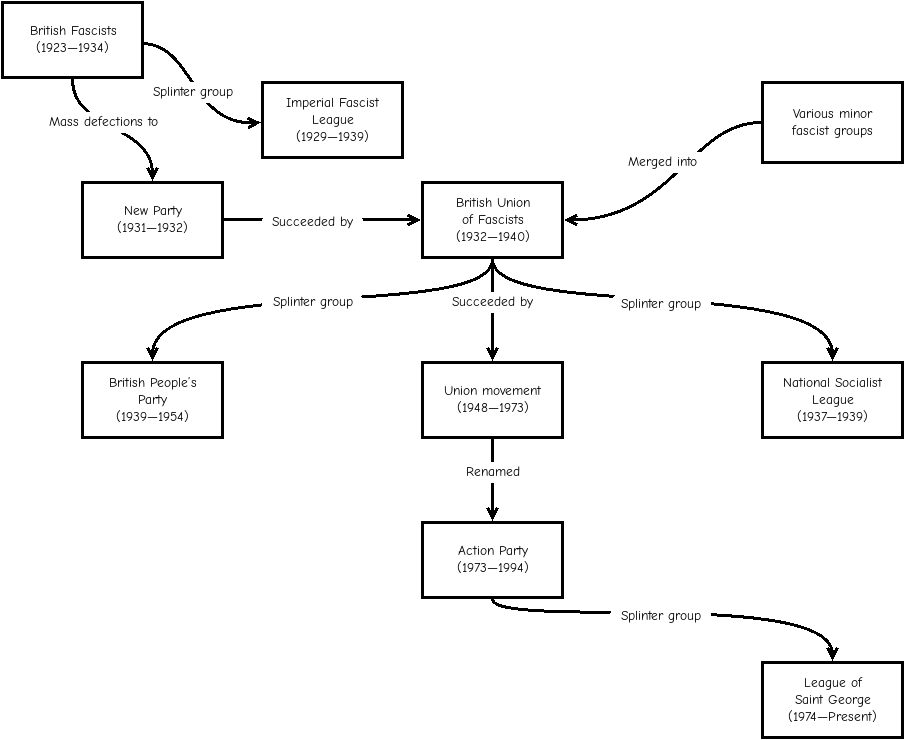

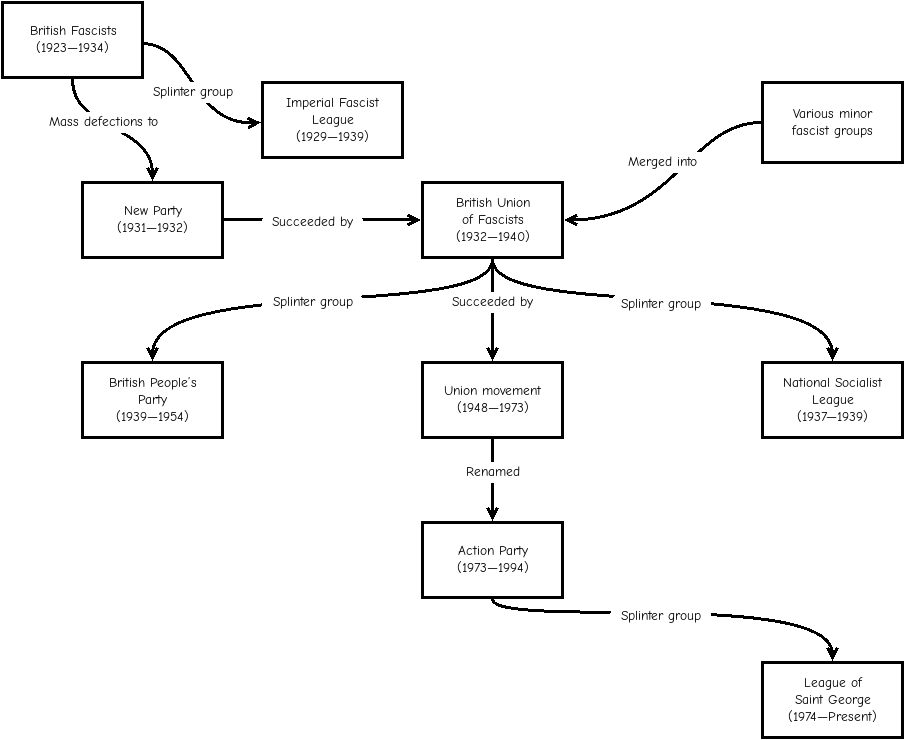

to leave it. In 1932, Mosley united most of the various British fascist organisations to form the British Union of Fascists

The British Union of Fascists (BUF) was a British fascist political party formed in 1932 by Oswald Mosley. Mosley changed its name to the British Union of Fascists and National Socialists in 1936 and, in 1937, to the British Union. In 1939, fo ...

into which the New Party subsumed itself. Out of the Scottish section was formed the Scottish Democratic Fascist Party

The Scottish Democratic Fascist Party (SDFP) or Scottish Fascist Democratic Party was a political party in Scotland. It was founded in 1933 out of the Scottish section of the New Party by William Weir Gilmour and Major Hume Sleigh.Kushner, Tony, a ...

, headed by William Weir Gilmour

William Weir Gilmour (1905–1998), was a Scottish politician who was associated with five different political parties; the Independent Labour Party, the New Party, the Scottish Democratic Fascist Party, the Labour and Co-operative party and the ...

.

An unrelated New Party was launched in Britain in 2003.

Election results

By-elections, 1929–1931

1931 UK general election

References

Sources

*Benewick R. '' The Fascist Movement in Britain'' (1972) * Dorril, Stephen. ''Blackshirt'', Viking Publishing, 2006 * Mandle, W.F. "The New Party," ''Historical Studies. Australia and New Zealand'' Vol.XII. Issue 47 (1966) * Pugh, Martin. ''Hurrah for the Blackshirts!': Fascists and Fascism in Britain between the Wars'', Random House, 2005, * Skidelsky, Robert "The Problem of Mosley. Why a Fascist Failed," ''Encounter'' (1969) 33#192 pp 77–88. * Skidelsky, Robert. ''Oswald Mosley'' (1975), the standard scholarly biography * Mosley, Oswald. ''My Life'' (1968) * Worley, Matthew. ''Oswald Mosley and the New Party'', Palgrave Macmillan, 2010,Primary sources

* Mosley, Oswald. ''A National Policy'' 1931 * Mosley, Oswald. ''Unemployment'' 1931 * Mosley, Oswald. ''The National Crisis'' 1931 * Mosley, Oswald; Mosley, Cynthia; Strachey, John; Baldwin, Oliver; Forgan, Robert; Allen, W.E.D. ''Why We Left The Old Parties'' 1931 * Davies, Sellick. ''Why I Joined The New Party'' 1931 * Joad, C.E.M. ''The Case For The New Party'' 1931 * MacDougall, James Dunlop. ''Disillusionment'' 1931 * Diston, Adam Marshall. ''The Sleeping Sickness of the Labour Party'' 1931 * Diston, Adam Marshall; Forgan, Robert. ''The New Party and the I.L.P.'' 1931 * Allen, W.E.D. '' The New Party and the Old Toryism'' 1931 {{Authority control Defunct political parties in the United Kingdom Labour Party (UK) breakaway groups Oswald Mosley Political parties established in 1931 Political parties disestablished in 1932 1931 establishments in the United Kingdom Syncretic political movements